|

| Query: Salamander | Result: 57th of 549 | |

Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum) <!--액솔로틀-->

| Subject: | Axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum)

| |

| Resolution: 514x444

File Size: 57556 Bytes

Upload Date: 2005:09:05 19:50:19

|

Captured from a WONDERFUL MULTIMEDIA CD-ROM title,

"Eyewitness Encyclopedia of Nature",

Dorling Kindersley Multimedia, 1995

Dorling Kindersly Multimedia

(reviewed by Univ. of Texsas Library)

http://volvo.gslis.utexas.edu/~reviews/dkmm.html

For more images captured from the CD-ROM title,

http://bioinfo.kordic.re.kr/animal/APAsrch2.cgi?qt=DKMMNature-

Ambystoma mexicanum

(axolotl)

By Amy Majchrzak

Kingdom: Animalia

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Class: Amphibia

Order: Caudata

Family: Ambystomatidae

Genus: Ambystoma

Species: Ambystoma mexicanum

Geographic Range

Ambystoma mexicanum is historically found in Lakes Chalco and Xochimilco of the Valley of Mexico near Mexico City, Mexico. (Brandon, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989; Smith, 1969; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Biogeographic Regions:

neotropical .

Habitat

Elevation

2290 m (average)

(7511.2 ft)

The native habitats of A. mexicanum are large, relatively permanent (until recently), high-altitude lakes located near Mexico City. Of the two lakes - Chalco and Xochimilco - where these animals are historically native, only Xochimilco (elevation: ~ 2,274 m) remains. Axolotls are almost extinct in their native habitat, largely due to the introduction of predatory fishes and habitat loss. (Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service, 2003; Shaffer, 1989)

These animals are found in the following types of habitat:

freshwater .

Aquatic Biomes:

lakes and ponds.

Physical Description

Mass

60 to 110 g; avg. 85 g

(2.11 to 3.87 oz; avg. 2.99 oz)

Length

30 cm (high); avg. 23 cm

(11.81 in; avg. 9.06 in)

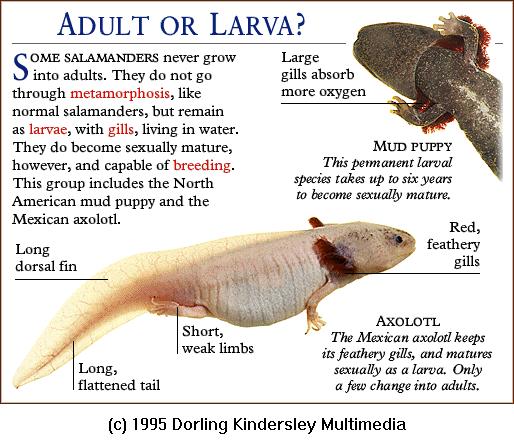

Axolotls are paedomorphic or neotenic aquatic salamanders, meaning they retain certain larval characteristics in the adult, reproductive state. They possess feathery external gills and finned tails for swimming. Laboratory animals exist in several color morphs, ranging from wild type (dark, mottled brownish-green) to albino. Axolotls reach lengths on average of 20 cm (9 inches), but can grow to more than 30 cm (12 inches) in length. (Brunst, 1955a)

The sexes can be easily distinguished in adult axolotls. Males can be identified by their enlarged cloaca (similar to other urodeles), while females have a smaller cloaca and round, plump bodies. (Brunst, 1955a)

Some key physical features:

ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry .

Sexual dimorphism: sexes shaped differently.

Development

A. mexicanum is paedomorphic, which means that it retains larval characteristics in the reproductively mature adult form. Juvenile and adult axolotls possess feathery, external gills and tail fins suited to an aquatic lifestyle. Metamorphosis can be induced in axolotls via thyroid hormone injections. In the wild, axolotls rarely, if ever, metamorphose.

neotenic/paedomorphic; metamorphosis .

Reproduction

Breeding interval

Axolotls in the wild breed once yearly.

Breeding/spawning season

Breeding laboratory axolotls can be accomplished at almost any time; in the wild, it is thought that the best time for spawning is March to June.

Number of offspring

100 to 300; avg. 200

Time to hatching

10 to 14 days

Time to independence

10 to 14 days

Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (female)

1 years (average)

Age at sexual or reproductive maturity (male)

1 years (average)

The courtship behavior of A. mexicanum follows the general Ambystoma pattern; it first involes each animal nudging the other's cloacal region, eventually leading to a "waltz," with both animals moving in a circle. Next, the male moves away while undulating the posterior part of his body and tail (resembling a "hula dance"), and the female follows. The male will deposit a spermatophore (a cone-shaped jelly mass with a sperm cap) by vigorously shaking his tail for about half a minute, and will then move forward one body length. The female then moves over the spermatophore, also shaking her tail, and picks up the spermatophore with her cloaca. (Eisthen, 1989)

Mating systems:

polygynandrous (promiscuous) .

Axolotls breed in the wild generally from March to June. From 100 to 300 eggs are deposited in the water and attached to substrates. Eggs hatch at 10 to 14 days and the young are immediately independent. Sexual maturity is reached in the next breeding season. (Eisthen, 1989)

Key reproductive features:

iteroparous ; seasonal breeding ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (internal ); oviparous .

Eggs are surrounded by a protective jelly coat and are laid singly, unlike frog eggs (which are laid in clumped masses), because they possess higher oxygen requirements. They are often attached to substrates such as rocks or floating vegetation.

Parental investment:

no parental involvement; pre-hatching/birth (provisioning: female).

Lifespan/Longevity

Expected laboratory longevity is 5 to 6 years; however, some animals have been known to live as long as 10 to 15 years. Most laboratory animals die shortly after metamorphosis. (Brunst, 1955a)

Behavior

Axolotls are solitary and may be active at any time of the day.

Key behaviors:

natatorial ; diurnal ; nocturnal ; motile ; sedentary ; solitary .

Communication and Perception

Axolotls communicate mainly via visual cues and chemical cues during mating. At other times of the year there is little to no intraspecific communication.

Axolotls can detect electrical fields and also use their vision and chemical cues to perceive their environment and discover prey.

Communicates with:

visual ; chemical .

Other communication keywords:

pheromones .

Perception channels:

visual ; chemical ; electric .

Food Habits

Generally the top predator in their natural environment, axolotls will eat anything that they can catch, including molluscs, fishes, and arthropods, as well as conspecifics. (Shaffer, 1989)

Primary Diet:

carnivore (piscivore , insectivore , eats non-insect arthropods, molluscivore ).

Animal Foods:

amphibians; fish; insects; mollusks; terrestrial worms; zooplankton .

Predation

Axolotls may be preyed on by large fish and conspecifics. Large fish have only recently been introduced into the lakes where axolotls are found, contributing to the demise of their populations.

Ecosystem Roles

Axolotls were the top predator in their native environment, making them important in structuring community dynamics.

Economic Importance for Humans: Negative

There are no negative effects of axolotls on humans.

Economic Importance for Humans: Positive

Axolotls are an important research animal and have been used in studies of the regulation of gene expression, embryology, neurobiology, and regeneration. Occasionally taken as a food item (substituted for fish), axolotls are prepared by either roasting or boiling and the tail is eaten with vinegar or cayenne pepper. They have also been used for medicinal purposes. (Brunst, 1955a; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Ways that people benefit from these animals:

pet trade ; food ; source of medicine or drug ; research and education.

Conservation Status

IUCN Red List: [link]:

Vulnerable.

CITES: [link]:

Appendix II.

The natural habitat of A. mexicanum is nearly gone. Historically, they have been known to live in high altitude lakes near Mexico City. Lake Chalco is gone completely, drained for drinking water, and Lake Xochimilco is now nothing more than a scattering of canals and swamps. Because known populations are few and far between, very little is known about the ecology and natural history of A. mexicanum; there have been few ecological studies on wild populations. (Brandon, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Other Comments

The word "axolotl" comes from the native Aztec language, or nahuatl. It roughly translates to: water slave, water servant, water sprite, water player, water monstrosity, water twin, or water dog. All of these names refer to the Aztec god Xolotl, brother to Quetzacoatl and patron of the dead and ressurrected (where he took the form of a dog), games, grotesque (read: ugly) beings, and twins. Aztec lore states that Xolotl transformed himself into, among other things, an axolotl to escape banishment. He was captured, killed, and used to feed the sun and moon. (Shaffer, 1989; Smith, 1969)

Larvae of other ambystomids, such as the larval stage of the tiger salamander, A. tigrinum, are often erroneously referred to as axolotls. The name axolotl should be used only when referring to A. mexicanum and not to any other ambystomid salamander. Historically, the Mexican axolotl has been listed under more than 40 different names and spellings; all, except A. mexicanum, have been rejected by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN). (Brunst, 1955a; Brunst, 1955b; Smith, 1969; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

The closest relative of A. mexicanum is thought to be A. tigrinum, the tiger salamander. Indeed, the larvae of these species are visually very similar. Some even consider the axolotl to be a subspecies of the tiger salamander; viable offspring can be produced between the two species in the laboratory, though no hybrids have as of yet been discovered in the wild. (Brandon, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989; Smith, 1969; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Axolotls are excellent lab specimens as they are easy to raise and inexpensive to feed. They are renowned for their amazing regenerative capabilities, have been used widely in developmental studies, and, because of their large cells (they are polyploid), are often used in histological studies. (Brunst, 1955a; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Nearly all modern laboratory axolotls can be traced back to 33 animals shipped from Xochimilco to Paris in 1864. They are one of the most widely used and studied laboratory animals. (Smith, 1969; Smith, Armstrong, and Malacinski, 1989)

Contributors

Amy Majchrzak (author), Michigan State University: October, 2003.

Tanya Dewey (editor), Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

References

Brandon, R., J. Armstrong, G. Malacinski. 1989. Natural history of the axolotl and its relationship to other ambystomid salamanders. Pp. 13-21 in Developmental biology of the axolotl. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc..

Brunst, V. 1955. The axolotl (Siredon mexicanum) I. As material for scientific research. Laboratory Investigation, 4: 45-64.

Brunst, V. 1955. The axolotl (Siredon mexicanum) II. Morphology and pathology. Laboratory Investigation, 4: 429-449.

Eisthen, H. 1989. Courtship and mating behavior in the axolotl. Axolotl Newsletter, 18: 18-19.

Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 2003. Xochimilco. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed 06/13/03 at http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?.eu=79786.

Shaffer, H. 1989. Natural history, ecology, and evolution of the Mexican "axolotls". Axolotl Newsletter, 18: 5-11.

Smith, H. 1969. The Mexican axolotl: some misconceptions and problems. BioScience, 19: 593-597.

Smith, H., J. Armstrong, G. Malacinski. 1989. Discovery of the axolotl and its early history in biological research. Pp. 3-12 in Developmental biology of the axolotl. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc..

|

Comments |

|---|

| | Guest |

|

Scientific Name: Ambystoma mexicanum (Shaw & Nodder, 1798)

Common Names: Axolotl, Mexican Salamander, Mexican Walking Fish, Salamandra ajolote [Spanish]

Synonyms: Gyrinus mexicanus Shaw and Nodder, 1798 |

^o^

Animal Pictures Archive for smart phones

^o^

|

|

|